A Conversation and UX Designer.

Aru

A responsive web-based knowledge community for parents of children with sensory complexities (often children with Autism Spectrum Disorder). The Aru community includes parents, caregivers, occupational therapists, pediatricians, and other related professionals. Aru’s user interface and dynamic AI system work together to provide parents a personalized information experience by serving up the answers relevant to their child’s unique situation.

Project

UW MHCI+D Capstone Project

Advisor

Intentional Futures

Roles

Lead Designer, Strategist, Researcher

Team

Amberly Riegler

Tiffanie Horne

At its core Aru is an information experience tailored to a niche population where parents can connect, find answers, and when they are ready pay it forward.

Product video with our real research participants!

What is Sensory complexity?

Sensory processing is the brain’s way of organizing and making sense of information received from your senses. It is particularly prevalent among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Sensory processing needs arise when the brain processes this information differently: imagine if life was always like this GIF (GIF from Spectrum News). These needs cause children to encounter difficulty participating in society. In order to thrive, these children require their parents to seek out early intervention on their behalf.

Approximately 3-9 million children have sensory processing disorder (SPD).

In our research, we found that the parents of children with sensory complexity deal with a lot of hardship. They feel like they cannot take their children out in public, they face increased healthcare costs, and often deal with misconception and social isolation. These families need support.

We strive to support parents of sensory sensitive children to provide their kids the ability to independently manage their sensory processing needs.

Design Solution

Unlike traditional social networking sites (e.g.Facebook) or a question-and-answer platforms (e.g.Quora), Aru facilitates information sharing by employing an AI recommender system and search engine. Aru’s recommender is an intelligent system that personalizes users’ feeds based upon self-identified preferences at onboarding as well as analyzing users’ usage over time.

Additionally, Aru’s search engine subtly guides users in creating and reformulating queries. Use as-you-type suggestions including auto-complete, auto-suggest, and instant results help users save time, iterate upon their searches, and get the results they want.

Aru

Aru emphasizes the complementary nature of forging connections and finding information. To define the Aru information experience, Aru holds the image of the friendly, informative, and reassuring librarian. Given that Aru provides support to parents of children with sensory complexities, visual elements of the Aru brand should reflect Person First Language (PFL) as defined by the CDC.

The Aru brand uses tonal words to convey Aru’s design principles in a consistent and relatable way. Aru’s tonal words include: warm-hearted, respectful, encouraging, informative and inclusive.

Aru's Design

In order to create a sense of comfort and community, Aru relies heavily on images, both product generated and user posted images. Each day, the landing page will show a new image that is associated with a tip of the day. The images will either contain a child or be directly related to children.

From a design perspective, I added this imagery element to contribute the feeling of close community as well as a something visually pleasing at the top of the page. Without it, the website was looking too bleak and and corporate, which was far from the intended tone we were going for.

Ethics and Privacy

Aru facilitates the sharing of important information to a sensitive user population. To foster a

safe environment and ensure the veracity of information, we created a set of guidelines which would be updated to remain aligned with best practices. They consist of ensuring that the community is always gated, nobody is allowed to make medical recommendations, and the AI system is always made transparent.

My team and I wrote these ethics rules to ensure that our product addressed all of the concerns that we could think of. We spend some time thinking of any possible unintended outcome or usage of the product and how we might be able to fix the problem before it happened. When possible, I build assurances into the design. But we also wanted to make sure that our design solution would be fluid enough to address any unintended consequences, and this set of guidelines does that.

The Design Process

So how did we get to Aru?

Everyone has their own preferred design process, commonly using the double diamond user-centered design model, but I believe that there should be more flexibility in it. Ultimately it boils down to designing the right thing and designing it right.

I use a malleable, iterative design process, taking context into account to come up with the best plan for research, ideation, prototyping, evaluation, and iteration. In this project, the process looked more like this:

Topic Selection

Something magical happens when three designers, one who loves art (me), the other biology,

and the other education, brainstorm ideas about how design can be used to make the world better. We all identified that we wanted to work on something that would actually help people and give us a feeling of "doing good." Neurodiversity (ND) quickly rose to the top of our list. ND is a concept that appreciates the fact that our brains function and are wired differently.

As we began to conduct secondary research, ND quickly turned into autism and SPD. None of us wanted to be designers who come into a community and design for them without strongly engaging with them, so we decided we would go into the community and try to meet some people. Day Out for Autism occurred right around that time, so my teammates and I volunteered at the event. The major takeaways from this event were:

1. There are a lot of resources out there for children with autism and SPD

2. But many of those resources are quite expensive

Research

We used multi-dimensional approach in conducting our research. During the research phase of this project, we talked with 10 people, 5 professionals and 5 parents. Our team divided the workload, so I was able to do a mix of conducting, note-taking, and photographing the interviews.

Our research consisted of semi-structured interviews, as well as artifact analysis and a creating toolkit of sensory toys. These activities allowed us to explore sensory needs on a professional and personal level in order to better understand the lived experience of families and fully inform future design direction.

I really enjoyed talking with the participants and gaining a strong knowledge base on the topic. I think that having a designer involved so deeply helped me think of the situation more holistically, incorporating all of the research insights and findings to create a better finished product.

My teammates and I with one of our research participants. He wanted to do the "W" for Washington hand with us!

Research Insights

Research Insights

Parents experience a sense of loss at identification that hinders acceptance and responsiveness.

"It took me from the first I heard it at 2 until he was 5 years old and had a formal diagnosis. I never would have thought it would be a diagnosis.” - April, parent

Research Insights

Parents lack support in navigating the massive amount of information to identify necessary interventions.

“Doctors don’t really help that much...the packet that they gave me with resources, 80% of it didn’t pertain to what I needed.” - Monica, parent

Research Insights

Advice from parents is valued above info from professionals because it allows new parents to identify and prioritize tried and true interventions.

“We get more from each other because everything is trial and error… You get more from ‘did you try this and this, or this worked for me, or this worked for my friend’. We get more out of that than from our therapist.” - Monica, parent

Design Principles

I translated these insights and findings into actionable design principles. As the lead designer on the team, I set the tone of the design, ensuring that the all of the design elements addressed concerns we identified in the research.

"Avoid othering" and "Accept and Encourage" served as internal team principles. Treating these families with respect was important to us, especially as designers who are entering the community only for a short time.

We took these principles to heart and used them as fuel for coming up with a plethora of ideas.

Design Principles

Circulate Stories

Give parents stories that show them what thriving kids with constantly evolving sensory processing needs looks like. The design should circulate personal stories of success that catalyze the parent’s towards trying new and creative solutions.

Design Principles

Create Efficiency

The design should expedite the process of finding effective interventions. New parents, in comparison to the recommendations received from professionals, are more likely to experience success when trying out an intervention received from the advice of a more experienced parent.

Design Principles

Avoid Othering

Emotional problems can be heightened when parents lack access to a community who understand and are familiar to the behaviors of children with sensory process needs. Design decisions should not further ostracize the parents.

Design Principles

Accept & Encourage

Parenting a child with sensory processing needs is a life-long adjustment and parents react differently. To support acceptance of this identification and advance providing necessary treatment the design should anticipate and acknowledge the parent’s emotional journey.

Design Principles

Forge Connections

Accessing and forming support networks eliminates isolation and leads to a community that insulates families from societal misconceptions and exposes many resources. The design should provide opportunities to build and link parents with other people who have a common understanding or similar experiences.

After our lengthy analysis, we took down all the post-its and had this giant pile...

Analysis

After our interview process was complete, we externalized our data onto post-it notes in order visualize and create a common language around our research findings. We then used affinity diagramming to identify themes within our data, which led to generation of insights and sense making artifacts.

As a designer I got a lot of value out of this process. Having a designer in the room during data decomposition was really helpful, both for me to learn more about the research process and to provide a different opinion on how to think about and organize our insights.

Ideation

Thanks to advice from our capstone advisor (Eric Lawrence, Intentional Futures), we began sketching and ideating while we were still in the research phase of this project. This forced us to be action oriented and forward thinking from day one. When the formative research finished, we began to dive deep into ideation so that we could come up with an idea for a product that would really address the findings of the research.

Since I was the sole designer on the team (and I love ideation/creating problem solving), I led a number of exercises to come up with an abundance of ideas. I've been creating my own set of preferred techniques (ask me about this!) and this allowed me to hone in on which work best. I believe that braiding and crazy 8s are some of my favorites, and they worked particularly well here.

A few quotes on sketching:

"The best way to a good idea is to have lots of ideas." - Linus Pauling

"A sketch is incomplete, somewhat vague, a low-fidelity representation. The degree of fidelity needs to match its purpose, a sketch should have 'just enough' fidelity for the current stage in argument building.... Too little fidelity and the argument is unclear. Too much fidelity and the argument appears to be over—done; decided" - Hugh Dubberly

Ideation Workshop

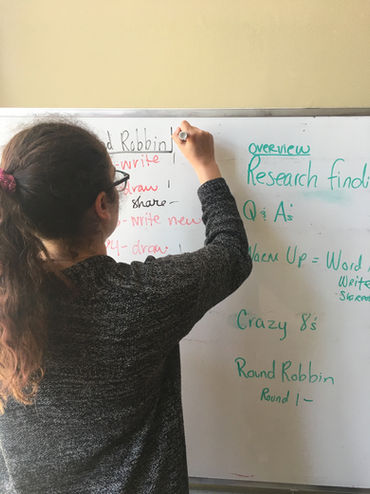

My team led a workshop with our classmates to increase our breadth of ideas and help us think outside the box. We spent an hour together and the time consisted of an intro on our research and findings, a word association exercise, crazy 8s, and then a round robin activity that I created.

I've been experimenting with brainstorming techniques, so I decided to create one of my own. I combined a couple of techniques that work well for me (round robin and braiding) and the results if this exercise was some interesting ideas!

Round Robin + Braiding

Write an idea on the top of a piece of paper. Hand that paper to the person next to you. Sketch the idea they came up with for 1 minute. Repeat. I came up with the idea of combining two brainstorming techniques to poke holes in people's ideas and force them to think about things in a different way. I was influenced by Buxton's idea that sketches are meant to be conversation starters. Buxton says "Sketches are intentionally ambiguous, and much of their value derives from their being able to be interpreted in different ways, and new relationships seen within them, even by the person who drew them." My thought was that the participants would start a conversation by putting their own spin on somebody else's idea and maybe this process would result in new, more unique ideas. I think that this technique worked really well and I would like to continue this in future projects!

Some images from the ideation workshop.

Narrowing

I mentioned earlier that we created a significant number of ideas to force ourselves to be creative and think outside the box. We ended up sketching over 150 unique ideas. A lot of the ideas were too small to be stand-alone products, but could easily fit together into a larger ecosystem.

Narrowing first consisted of comparing each idea to the design principles (see above) and then eliminating anything that did not adhere to them. We combined similar ideas to make them stronger and then we sorted the concepts by how they would help families (advice, tracking, learning, trying). Team understanding of the space, intuition, and further combining lead us to 6 ideas that we were excited about.

Tiffanie and I organizing our sketches by category.

Storyboarding

We created storyboards for these 6 narrowed ideas. Our storyboards allowed us to see how the idea might play out over time and understand how it could fit into the lives of the users.

I am a big fan of using storyboards for both internal and external understanding and buy-off. I recently read a post on invision's blog titled Scrap the user persona. Replace it with the storyboard. and I really connected with this idea. Personas can so easily get stuck in simplified and stereotypes of users and I believe that storyboards give a better understanding of the complexity of people, products, and ideas.

The article says "As humans, we are hardwired to understand and interpret stories. Stories are the way we share empathy in our culture. The great thing about stories is they can capture many different types of situations. Everyone has a story, a set of struggles and anxieties, and we need to capture this information to better serve them."

Some interesting ideas/stories for this project were a travelling sensory story sharing exhibit, a network of hacking/DIY advice, and sensory pen pals. Creating storyboards for each of these ideas allowed us to see them more holistically, and how they might play out over time. Since we wanted to help as many parents as we could, we placed high emphasis on ideas that would be applicable at multiple stages of the parents journey.

The 6 storyboards. I personally created the upper left and right ones.

After critique, we decided to further combine our ideas and compress them into a single idea revolving around micro-communities. This concept focuses on forging connections between families dealing with sensory processing needs. This was driven by our insights, which included parents struggling to make connections and the value of those connections, like finding access to support networks and receiving advice from that community.

Prototype 1: Micro Communities

In this idea, parents would be paired with a small group of individuals similar to them in order to facilitate exchange and support. All members of the community would have similarities, such as location, child’s symptoms, or child’s age. The parents could use the micro-community platform to talk, as questions, and share advice, events, and even items they do not need anymore.

The focus of the first round of prototype testing was purely focused on concept validation. We wanted the type of prototype and its fidelity to match the feedback we were looking for, so we decided that a storyboard would be best. I believe in prototyping at various levels of fidelity and different prototyping methods (not just product mockups) so I created a plan for the different prototypes I would make at different stages of the design, ensuring that the method matched the type of feedback we wanted to receive. I opted for storyboarding as the first prototype because it would allow the participants to have a better understanding of the idea and visualize themselves in the place of the person in the storyboard.

We interviewed 4 parents and asked them about to evaluate our prototype and compare it to their experience dealing with children with sensory processing needs.

From that testing we learned that parent’s didn’t want to be forced to talk to other parents within groups, and they found the information from other parents was more valuable than making personal connections.

"It's a community to bounce ideas off of, it's the advice. I don't need more friends." - research participant

Prototype 2: Q&A Platform

Based on the feedback from the first prototype testing, we knew we had to switch things up. The idea of micro-communities was conservatively accepted by the participants, but we found that the information seeking was more important than meeting people and creating a community. So what if we put the information first? What do people most want to do when they have a concern for their child? Get specific help and not have it take too long.

This concept is for a secure and supportive space that connects parents to pertinent information. The community is the backend for how parents find the information. Each parent self-identifies their needs and experience and the system displays questions that they would either know the answer to or want to know the answer to. Thus, they can quickly find pertinent advice and/or help other people.

This prototype is a low fidelity wireframe clickthrough. The focus of the testing was on usability and understanding how the participants would engage with the product (would they search? Ask? Browse?) so I decided to focus my energy on building out all of the screens needed for a fully fleshed out scenario. I believe that this was a good choice because I tend to get better, more honest feedback when doing testing at a low-fi level and we wanted complete honesty!

From testing, we found searching to be most relevant interaction. So we knew the next prototype to enhance the visibility and functionality of the search feature.

Also, parents told us the platform lacks life. In removing the micro community from the idea, we stripped the community out too much. So we needed to expose more of the activity and usage by other parents.

Logo

Aru is a loose translation of the Japanese word for owl. These graceful birds are often associated with learning and wisdom. We chose an owl inspired logo and name because Aru harnesses the wisdom of its users to share information and advice across a community. Aru also looks and sounds very similar to “are you,” which is a play on the fact that this platform is used to share questions.

The logo was designed to conjure an owl as well as Q and A. It embraces the curves and soft edges that are used throughout Aru. It also mimics the never-ending, circular journey that parents go through when dealing with sensory complexity.

Color Palette

Our primary gradient color is purple, conveying trustworthiness and wisdom. The gradient represents the spectrum of manifestations within sensory processing disorder. It also mimics the range of how someone with a sensory complexities perceives stimuli - from hypersensitivity to hyposensitivity.

The primary solid color is a vibrant teal. Blue connotes security and confidence.

The chosen primary colors are complementary and contribute to an optimistic and encouraging aesthetic. Warm shades were chosen to add a sense of comfort. Parenting children with sensory complexity is hard, and Aru should feel like a welcoming, safe space.

Iconography

Aru’s icons are calming, friendly, and wise.

The iconography used in Aru is simple and is paired with a written description to maximize clarity for the user. If the description is not shown outright, it will be visible on hover.

Icons were chosen to reflect current industry standards. They were user tested and only those that were consistently understood were incorporated into Aru’s design. This ensures Aru is easy to use.

Unique to Aru is the lifeguard floatation icon. I created this icon because the advice parents receive from other community members can feel like a lifesaver, therefore this icon was chosen to help indicate advice parents found helpful.

Takeaways

One of the earliest takeaways we had with this project was learning how to interact with and talk about people from sensitive communities. We wanted to be respectful, and this is reflected in the design principles we created.

To me, the inclusivity that we tried to utilize throughout the process was really important. Our world often takes a neurotypical viewpoint, and thinking through a lens of inclusivity and diversity can be incredibly powerful.

Also, getting multiple perspectives from each other, learning methods from both industry and academia really allowed us to see multiple ways to address problems and process. This gave us the context to step back and create our own way of working which we found very enriching